Please note that this chapter contains sexually explicit and violent images and text. If you strongly object to any of these images please contact the blog author at vittoriocarvelli1997@gmail.com and the offending material can be removed. Equally please do not view this chapter if such material may offend.

This is a revised and updated version of the 'Story of Gracchus'

Vigil - 'Eclogue'

Unlike Roman citizens, slaves could be subjected to corporal punishment (whipping and beating), sexual exploitation (both female and male prostitutes were often slaves), torture, and summary execution.

Within the empire, slaves were sold at public auction or sometimes in shops, or by private sale in the case of more valuable slaves.

One particular class of male slave was the the 'puer delicatus' - a handsome slave-boy, chosen by his master for his boyish beauty.

In the Satyricon, by Petronius, the tastelessly wealthy freedman Trimalchio says that as a slave-boy he had been a 'puer delicatus', servicing both the master and the mistress of the household.

No moral censure was directed at the man who enjoyed sex acts with either females or males of inferior status (usually slaves), as long as his behaviours did nor infringed on the rights and prerogatives of his masculine peers.

The "conquest mentality" was part of a "cult of virility" that particularly shaped Roman 'male on male' practices.

These 'Followers of the Way' were part of the religious phenomena referred to a 'mystery religions', which were a prominent feature of Roman and Hellenistic society.

In order to produce a believable and, where possible, a realistic story, it has been deemed necessary to reconstruct, in the imagination of both author and reader, Roman society.

Rome was originally a small village on the banks of the River Tiber.

As the years passed, the sheer aggression and drive of the original settlers forged a vast Empire (which in the end they were completely unable to control or direct).

The reason for Rome's aggressive and thrusting rise to power lay in the Roman attitude to morality, which they had inherited from the 'heroic age' of the Hellenic world.

In this 'heroic' morality, (perfectly described in the wrings of the German philosopher Frederich Nietzsche - left) ‘good’ picks out exalted and proud states of mind, and it therefore refers to people, not actions, in the first instance.

‘Bad’ means ‘lowly’, ‘despicable’, and refers to people who are petty, cowardly, or concerned with what is useful, rather than what is grand or great.

Good-bad identifies a hierarchy of people, the noble masters or aristocracy, and the common people. - in Rome the patricians and the plebeians.

The noble person only recognizes moral duties towards their equals; how they treat people below them is not a matter of morality at all - and this, of course lies at the basis of slavery - a key theme in the 'Story of Gracchus'.

The good, noble person has a sense of ‘fullness’ – of power, wealth, and ability.

From the ‘overflowing’ of these qualities, not from pity, they will help other people, including people below them.

Noble people experience themselves as the origin of value, deciding what is good or not.

‘Good’ originates in self-affirmation, a celebration of one’s own greatness and power.

They revere themselves, and have a devotion for whatever is great.

But this is not self-indulgence: any signs of weakness are despised, and harshness and severity are respected.

A noble morality is a morality of gratitude and vengeance.

Friendship involves mutual respect, and a rejection of over-familiarity, while enemies are necessary, in order to vent feelings of envy, aggression and arrogance.

All these qualities mean that the good person rightly evokes fear in those who are not their equal and a respectful distance in those who are.

This struggle between masters and slaves recurs historically.

According to Nietzsche, ancient Greek and Roman societies were grounded in master morality.

The Homeric hero is the strong-willed man, and the classical roots of the Iliad and Odyssey exemplified Nietzsche's master morality.

Historically, master morality was defeated as the vicious 'slave morality' of Christianity spread throughout the Roman Empire.

In attempting to reconstruct Roman society, it is essential to take into account the immense significance that religion had on Roman attitudes to all aspects of life, from marriage, to sexuality, the family and the home, and most significantly the political decisions taken by the state.

Roman religion was basically 'syncretic', deriving many features from the cults of Latium, Eturia and Alba Longa - the precursor of Rome.

In addition there was the influence of Greek colonies in the south of the Italian peninsular.

From a range of deities adopted from the Greeks, the Romans altered the gods' identities, but left their characters unchanged.

The Greek king of the gods, Zeus, was in Rome the god Jupiter.

Hera was called Juno, Aphrodite was called Venus.

Most of the Greek gods could be found in Rome: going through the same drama, the same complications and conflicts.

Both cultures, Greek and Roman, incorporated the idea that the gods were susceptible to making mistakes, much like humans.

Gods and goddesses were just as likely to fall into temptation as mortals, in fact, Roman gods were even prone to sexual liaisons, both heterosexual and homosexual, as their Greek counterparts.

Beginning in the culture of the Greeks, and then moving onward through that of the ancient Romans, there was also a tangled parallelism of human and divine action.

In the absence of rational explanations for what the people of these cultures witnessed around them, it seemed as if everything that happened, good or bad, was due to the intervention of the gods.

Military triumphs were seen as a sign of the celestial rewards, regardless of the comparative strength of the armies involved.

Defeats were seen as an example of divine retribution, and an indication that certain gods demanded to be appeased.

During the intense battle sequences depicted in the last book of 'The Aeneid', Aeneas is badly injured. For a moment, it looks as if he would not survive.

However, instead of leaving it to happen naturally, Aeneas' mother, the goddess Venus, intervenes.

There were all types of religious and mythological examples found sprinkled throughout Virgil's epic, all leading to the adoption of the mythology and beliefs of the Greeks by Roman society.

Even the fables, actions, and faults have a direct correlation to those that had been believed in Hellas (Greece).

To the Romans, religion was less a spiritual experience than a contractual relationship between mankind and the forces which were believed to control people's existence and well-being.

The result of such religious attitudes were two things: a state cult, which was a significant influence on political and military events of which outlasted the republic, continuing on into the Empire and Principate, and a private concern, in which the head of the family oversaw the domestic rituals and prayers in the same way as the representatives of the people performed the public ceremonials.

As has been stated, to the Roman mind, there was a sacred contract between the gods and the mortals. As part of this agreement each side would provide, as well as receive, services.

The role of the mortal in this partnership with the gods was to worship the gods.

The Romans had many gods of Etruscan origin - one being the goddess Furrina.

All anyone knew was that she was terrible, and thirsty for blood.

Even Cicero could but vaguely guess that she might have been a 'Fury', and yet she had her own flamen (priest), her own priesthood, as befit one who had been one of the first 13 gods of Rome.

Before the Greeks came with their bright, sunlit versions of the myths, the Romans had their own worship.

The three first gods of Rome were bloody Mars (to whom the victorious horse in the Campus Martius chariot races was sacrificed every October 15), death-dealing Jupiter (see above), and Quirinus, a fertility god of sanguinary aspect. (Quirinus’s plant was the myrtle, which prophetically runs with blood when Aeneas plucks it in Book III of Virgil's 'Aeneid'.)

Quirinus’s Quirinal Hill was apparently more prone than most to rains of blood.

Older even than those gods was Terminus, the god of boundaries.

His stone stood on the Capitoline Hill before anything else had been built.

By 500 BCE, the stone stood in the middle of a temple of Jupiter (Jupiter's Stone).

Terminus had refused to move, even for the king of the gods.

His lesser Termini were everywhere that a boundary or cornerstone was needed.

Each Terminal stone rested in a consecrated pit, one where priests had poured blood and ashes; every February 23, on the Terminalia, the stones of Terminus once more drank sacrificial blood.

The Termini remind us of the baetyls, sacred stones inhabited by gods, and perhaps also that Augustus’s first obelisk was made of blood-colored crystalline Imperial porphyry, the same as a pharaoh’s sarcophagus.

Did the stones of Rome move at night, or did some of its statues (of marble cold as death) refresh their vermilion and ocher paint with human gore? Something did.

According to Pausanias, the children of Medea returned from the dead and prowled Corinth - until the city fathers erected a statue of a Lamia.

Something also was reputed to prowl the Roman night - the 'Lemures', the restless dead.

Ovid writes that that “the ancient ritual” of 'Lemuria' “must be performed at night; these dark hours will present due oblations to the silent Shades.”

By Ovid’s time, the ancient ritual consisted of dropping beans behind you and not looking back.

Lemuria took place over three nights in May, which the Etruscans named Amphire.

Amphire (or Ampile) is cognate with Greek ampellos, 'vine', and Roman wine was thick, and sticky and dark red - like blood.

The Romans made the same connection: the Flamen Dialis, the priest of Jupiter, could not drink blood, or eat raw meat or pass under an arbour-vine.

And the Romans feared and embraced Bacchus, the god of wine and of “all the flowing liquids,” in the words of Plutarch.

The Greeks called him Dionysus, with epithets such as Omadius (“Eater of Raw Flesh”), Nyctelius (“God of Night”) and Anthroporraestus (“Man-Slayer”), and knew him also as the god of frenzy and possession, hence as the god of drama.

The Dacians called him 'Zalmoxis', and knew he lived among the dead.

They impaled a human sacrifice every five years to carry him messages.

Be he Dionysus, or Zalmoxis or Bacchus, Rome embraced him.

Almost too fervently at times; the Senate rounded up 7,000 Bacchantes for treason, illicit rites and gross immorality in 186 BCE.

Among the Bacchantes too influential to exile or execute were the Piso family.

They survived and flourished; Julius Caesar’s third wife, Calpurnia, was a Piso.

The Pisonians plotted against Nero to restore the Republic, (just before our story begins) and interestingly, as devotees of the god of the theatre, their conspiracy had some murky connection to the playwright Seneca.

SACRIFICE

Essential to the Roman concept of worship was prayer and sacrifice, and for both of these activities there were firmly defined rituals.

To perform these ritual correctly was of paramount importance.

One mistake and one would have to begin all over again.

The very nature of Roman religion itself, with its numerous gods, many of which had multiple roles, was cause for problems.

Particularly as in some cases not even the sex of a deity was clear.

Hence the phrase 'whether you be god or goddess' was a widespread in the worship of certain deities.

Many Roman gods also had entire collection of additional names, according to what aspect of life they were a patron to.

So, for example Juno was 'Juno Lucina', in her role of goddess of childbirth, but as goddess of the mint she was known as 'Juno Moneta', (this curious role came about because for a long time the Roman state mint was housed in her temple on the Capitoline hill).

For the official rituals of the state gods it was animals which most of the time were sacrificed, and for each god there would be different animals.

For Janus one sacrificed a ram - for Jupiter it was a heifer (a heifer is a young cow which has not yet had more than one calf).

Mars demanded a ox, a pig and or sheep, except for 15 October when it had to be the winning race horse of the day (the near side horse of a chariot team).

Such animal sacrifices were by their mere nature very elaborate and bloody affairs.

The animal's head had wine and sacred bread sprinkled over it.

The animal was killed by having its throat cut.

It was also disembowelled, for inspection of its internal organs for omens.

The most important organs of the dead beast would then be burnt on the altar.

The rest of the animal was then either moved away, or later eaten as part of a feast.

A priest would then say prayers, or better he would whisper them.

This too was a closely guarded ritual, by which the priest himself would be wearing some form of mask or blindfold to protect his eyes from seeing any evil, and a flute would be played to drown out any evil sounds.

Should anything about the sacrifice go wrong, then it had to be repeated, but only after another, additional, sacrifice had been made to allay any anger of the god about the failure of the first one.

For this purpose one would usually sacrifice a pig.

Thereafter the real sacrifice would be repeated.

Roman religion did not as such really practice human sacrifice.

Although it was not totally unknown. in the third and the second century BC it was the case that slaves were walled up underground by demand of the 'Sibylline Books'.

Also the gladiatorial Munera were a form of sacrifice to the dead.

In 'The Story of Gracchus', Markos' (later called Marcus) first banquet at the Villa Auri - to celebrate the birthday of Augustus Caesar - begins with sacrifices to Mars Ultor, Venus, the Divine Augustus and Mercury, and also features a Munera (see Chapter X) involving three pairs of gladiators.

A further Munera - on a grander scale, follows later in the story (see Chapter XXXI)

In 'Naturales Quaestiones' (Natural Questions), Seneca writes, “Some say that they themselves suspect that there is actually in blood a certain force potent to avert and repel a rain cloud.”

Or to draw one: like calling to like, as below, so above.

High on the hilltops priests of the gods raise their faces to the heavens, waiting for the fat red drops to hit.

The first known rain of blood on Rome occurred during the reign of Romulus, in 737 BCE.

From that time, rains of blood seem to have been regular, though never normal, occurrences, a portent recorded when such things could be spoken of aloud.

Repeated rains of blood fell on the Volcanal, a shrine to Vulcan on the slope of Capitoline Hill.

('I am quite aware that the spirit of indifference which in these days makes men refuse to believe that the gods warn us through portents, also prevents any portents whatever from being either made public or recorded in the annals. But as I narrate the events of ancient times I find myself possessed by the ancient spirit.… Two distinct portents had appeared in the Temple of Fortuna Primigenia on the Quirinal Hill: a palm tree sprang up in the temple precinct and a rain of blood had fallen in the daytime. — Livy, History of Rome - date of such a rain as 181 BCE.)

There was a rain of blood on the Comitium, at the Forum and at the Capitol in 197 BCE during the Macedonian War, and again in 183 BCE, the year Hannibal (lord of the child-burning cult of Carthage) died.

At his approach, the sacred shields of Fortuna in Praeneste sweated blood.

But as Livy mentions above, at some point the portents were no longer “made public or recorded in the annals.”

Perhaps they had become too gruesome, or too frequent for even Imperial historians to dare mention.

But the Romans still knew.

They poured their blood offerings out to the spirits of their ancestors, and to certain of their gods.

The Romans did so in increasing silence, and with increasing circumspection.

They might offer the blood libation into a lake that was known to communicate with the underworld, if they had country estates where such things were situated.

Or, if the Romans were city folk, they had the greatest, most blood-drenched shrine in the world all around them.

ORACLES & AUGURY

Of particular significance in Roman religion was the concept of augury.

According to ancient sources the use of auspices as a means to decipher the will of the gods was more ancient than Rome itself.

The use of the word is usually associated with Latins, though the act of observing Auspices is also attributed to the Etruscans.

Cicero describes in 'De Divinatione' several differences between the auspicial of the Romans and the Etruscan system of interpreting the will of the gods.

Though auspices were prevalent before the Romans, Romans are often linked with auspices because of both their connection to Rome’s foundation and because Romans were the first to take the system and lay out such fixed and fundamental rules for the reading of auspices that it remained an essential part of Roman culture.

Stoics, for instance, maintained that if there are gods, they care for men, and that if they care for men they must send them signs of their will.

Associated with augurs are the oracles of the gods.

These were numerous, and in some cases renowned in Greece, and included the famous oracle of Apollo at Delphi.

The Romans had their own oracle of Apollo, in this case situated at Cumae, in the person of the Cumaen Sibyl.

Cumae, of course, is very close to Baiae, where, in 'The Story of Gracchus', the Villa Auri is situated and, in the story, Gnaeus Gracchus visits Cumae twice, and receives a significant oracular messages from the Sibyl.

So ..... when reading the full version of the 'Story of Gracchus', it is wise to take into consideration the great differences between Roman society in the early empire, and current European and American society.

What may seem to us to be immoral, and maybe cruel and sadistic was, to the Romans, simply normal and acceptable behaviour.

This story, therefore, makes no attempt to criticize, condemn or ignore Greco-Roman mores and values, and the narrative accepts, and presents unreservedly the cultural 'status quo' of the times.

If you have any qualms about this, then perhaps this is not a story for you.....

if not... then go to the raunchy, realistic and, a far as possible, an historically accurate serial novel, featuring the adventures of young Markos.

'Now is the last age of the song of Cumæ - and the great line of the centuries begins anew.Now Virgo, and the reign of Saturn returns;now a new generation descends from heaven on high.A second Tiphys shall then arise, and a second Argo, to carry chosen heroes; and a second warfare too, there shall be, - and again great Achilles shall be sent to Troy.'

- And now, Marcus again leaves Athens for Rome, Gracchus shall once more die a bloody death, Petronius shall ever smile,and a little owl and a faun shall watch over the golden boy from the sea....and all shall be retold - time without end,as the Sybil weaves her endless magical spell....

Vigil - 'Eclogue'

|

| Virgil OUR STORY |

Our story is an attempt to bring just a small part of the world of that great empire to life - without the fantasy and unreality that has dogged so many tales set in that time,

The story of Gracchus, which features the slave-boy Markos, is set at a time around the end of the reign of the Emperor Nero.

|

| Nerō Claudius Caesar Germanicus |

|

| Gaius Octavian Augustus |

After the collapse of the Republic, the Empire, under the leadership of Gaius Octavian Augustus - the Princeps (emperor), - had enjoyed a sustained period of peace, prosperity and growth, (the 'Pax Romana'), and this continued under his adopted heir Tiberius.

There then followed the brief, but in some ways chaotic reign of Caligula, followed by the relative peace and stability of the Principate of Claudius. More disruption, however, followed with the reign of philhellene, Nero.

This period - from Augustus to the death of Nero - is usually referred to as the 'Principate of the early Empire', to distinguish it from the Republic, and the even earlier Kingdom of Rome.

It should be borne in mind, when reading this account (the fictional 'Story of Gracchus'), that the culture of Rome, while superficially familiar to us, was in fact radically different in many aspects to European and American culture as they stand today.

ROMAN SLAVERY

Central to the 'Story of Gracchus' is the concept of slavery.

|

| Cilician Pirates |

|

| Gaius Aelius - Hung and Emasculated |

Our story begins with a young freeborn Roman boy setting off on his first journey from Athens (where he has been living with his parents), to Rome.

On the voyage the ship in which they are travelling is attacked by pirates, the boy's parents are horribly murdered, and the boy (taken mistakenly to be a Greek slave boy) is taken to Crete, where he is sold to a Greek slave dealer.

|

| Marcus is Sold as a Slave |

Left overnight in the slave-pens of Crete the boy is then taken to Brundisium.

After a long and detailed interview with the slave dealer Arion, in which Marcus unsuccessfully pleads that he is a free-born Roman citizen, he is auctioned the following morning, and sold to the representative (Terentius) of a fabulously wealthy aristocrat called Gnaeus Octavian Gracchus.

The boy in question is Marcus Aelius - son of Gaius Agrippa Aelius.

After being sold as a slave, however, he is known as 'Markos' - the Greek version of his first name - and the Story of Gracchus is his story.

TYPES of SLAVES

The general Latin word for slave was 'servus'.

Slavery in ancient Rome played an essential role in society, and the economy.

Besides manual labour, slaves performed many domestic services, and might be employed at highly skilled jobs and professions.

Teachers, accountants, and physicians were often slaves.

Agathon appears in the 'Story of Gracchus' as a Greek slave, employed as a physician by Gracchus.

Greek slaves in particular, (and Markos was thought to be a Greek slave) might be highly educated.

Unskilled slaves, or those sentenced to slavery as punishment, worked on farms, in mines, and at mills, or were used in the arena.

Their living conditions were brutal, and their lives short.

LEGAL STATUS of SLAVES

It is important to understand that slaves were considered simply as property under Roman law, and had no legal 'person-hood'.

|

| Execution of a Runaway Slave |

|

| Marcus as the Slave 'Markos' naked and with a slave-collar |

Roman slaves could, however, hold property which, despite the fact that it belonged to their masters, they were allowed to use as if it were their own.

Therefore, highly skilled, or educated slaves were allowed to earn their own money, and might hope to save enough, eventually, to buy their freedom.

Such slaves were often freed by the terms of their master's will, or for services rendered.

Rome differed from Greek city-states, and other ancient societies, in allowing freed slaves to become citizens.

|

| Terentius |

After 'manumission', a male slave, who had belonged to a Roman citizen, enjoyed not only passive freedom from ownership, but active political freedom (libertas), including the right to vote.

A slave who had acquired 'libertas' was thus a 'libertus' ("freed person," feminine liberta) in relation to his former master, who then became his patron (patronus).

Terentius appears in 'The Story of Gracchus' as a slave who has undergone manumission.

Being a freedman, he appears in the story as a 'client' of Gracchus (who is his 'patron'), and in this situation, Terentius is expected to work for Gracchus - in this case as his secretary and the supervisor of Gracchus' slaves.

If, however, a master freed a slave in his will on death, and left no heirs, but rather allowed the freed slave to inherit the master's wealth and property, then the newly freed citizen (the 'ex-slave') could choose a patron, if he so wished - and would be truly free.

SOURCES of SLAVES & BUYING & SELLING

A major source of slaves had been Roman military expansion during the Republic.

The use of former soldiers as slaves led perhaps inevitably to a series of en masse armed rebellions, the 'Servile Wars', the last of which was led by Spartacus.

During the 'Pax Romana' (see above) of the early Roman Empire (1st–2nd century CE), emphasis was placed on maintaining stability, and the lack of new territorial conquests dried up this supply line of human trafficking.

To maintain an enslaved work force, increased legal restrictions on freeing slaves were put into place. Escaped slaves would be hunted down and returned (often for a reward).

One of the problems regarding the re-capture of slaves was the fact that slaves were not immediately identifiable in the general population.

|

| Silver Slave Collar |

Normally they wore no special clothing (except some slaves of high status masters, who might wear the master's livery).

Some masters, (like Gracchus in 'The Story of Gracchus'), required slaves to wear a distinctive 'slave collar', (usually thin and made of iron).

The slave collars used by Gracchus, however, (in 'The Story of Gracchus'), were unique, in being very heavy, and made of silver, with a distinctive medallion.

It is also worth noting that the majority of household slaves were allowed to mix with the general population in the towns and cities of the empire, and were not confined the the master's domus or villa.

New slaves were primarily acquired by wholesale dealers who followed the Roman armies.

Many people who bought slaves wanted strong slaves, mostly men.

Julius Caesar once sold the entire population of a conquered region in Gaul, no fewer than 53,000 people, to slave dealers on the spot.

|

| Slave-Boy |

|

| 'The Slave Market' - Gustave Boulange |

Slave dealing was overseen by the Roman fiscal officials called quaestors.

Usually, around the neck of each slave for sale hung a small plaque or scroll, describing his or her origin, health, character, intelligence, education, and other information pertinent to purchasers.

Prices varied with age and quality, with the most valuable slaves fetching prices equivalent to thousands of today's dollars.

Adult slaves were expensive, but the highest prices were paid for teenage slaves of both sexes, and in particular, well-educated, handsome young boys.

Because the Romans wanted to know exactly what they were buying, regardless of age or sex, slaves were presented naked.

The dealer was required to take a slave back within six months if the slave had defects that were not manifest at the sale, or make good the buyer's loss.

MASTER and SLAVE RELATIONS

Sexuality (see below) was a "core feature" of ancient Roman slavery.

Because slaves were regarded as 'property' under Roman law, an owner could use them for sex or hire them out to sexually 'service' other people.

The letters of Cicero have suggested that he had a long-term sexual relationship with his male slave Tiro.

The Roman 'paterfamilias' (father of the house) was an absolute master, and he exercised a power outside any control of society and the state.

In this situation there was no reason why he should he refrain having sexual relations his houseboys.

But this form of sexual release held little erotic cachet.

In describing the ideal partner in 'pederasty' (sex with boys), Martial prefers a slave-boy who "acts more like a free man than his master," that is, one who can frame the affair as a stimulating game of courtship.

|

| Sporus |

|

| Apollonian Ephebe |

Unlike the freeborn Greek eromenos ("beloved"), who was protected by social custom, the Roman 'delicatus' was in a physically and morally vulnerable position.

The "coercive and exploitative" relationship between the Roman master and the 'delicatus', who might be prepubescent, can be characterized in some cases as pedophilic, in contrast to Greek paiderasteia.

The boy was sometimes castrated in an effort to preserve his youthful qualities; the emperor Nero had a 'puer' named Sporus, whom he castrated and 'married'.

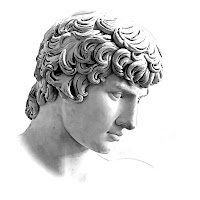

A somewhat more mature version of the 'puer delicatus' was the Emperor Hadrian's 'Antinous', who mysteriously died before he reached maturity.

The beauty of the Pueri was measured by Apollonian standards, - not too muscular, with smooth, pale skin, and absolutely no body-hair, with relatively small (uncircumcised) genitalia, but with beautiful wavy hair, if possible fair in colour.

The mythological type of the 'delicatus' was represented by Ganymede, the Trojan youth abducted by Jove (Greek Zeus) to be his divine companion and cup-bearer.

(In Chapter VIII of 'The Story of Gracchus', Markos is given the title of 'cup-bearer' by Gracchus).

|

| Silver 'Penis Cage' |

|

| Agathon |

A slave's sexuality was closely controlled, and normally slaves were no permitted to engage in sexual activity without their master's permission or knowledge.

In the 'Story of Gracchus', Terentius instructs the Greek physician, Agathon, to fit Markos with a silver 'penis cage', in order to prevent him for engaging in penetrative or oral sex, or even masturbating.

This device, however, is regularly removed so that Markos can have sex with another slave, Cleon, who has been specially selected to 'service' him at regular intervals.

|

| Cleon |

Slaves had no right to legal marriage (conubium), though they could, with permission, live together as husband and wife (contubernales).

An owner usually restricted the heterosexual activities of his male slaves to females he also owned; any children born from these unions added to his wealth.

Cato, at a time when Rome's large-scale slave economy was still in early development, thought it good practice to monitor his slaves' sex lives, and required male slaves to pay a fee for access to their fellow slaves.

Despite the external controls and restrictions placed on a slave's sexuality, Roman art and literature perversely often portray slaves as lascivious, voyeuristic, and even sexually knowing.

ROMAN SEXUALITY

Interestingly, at the root of this virile 'master morality' was the Greco-Roman concept of sexuality.

It is essential to note that Roman society was 'patriarchal' and 'phallocentric', and 'masculinity' was premised on a capacity for governing oneself, and others of lower status, not only in war and politics, but also in sexual relations.

|

| The 'Warren' Cup |

'Virtus', "virtue", was an active masculine ideal of self-discipline, related to the Latin word for "man", 'vir'.

It should also be noted that sexual attitudes and behaviours in ancient Roman culture differ markedly from those in later Western societies.

Roman religion promoted sexuality as an aspect of prosperity for the state - prostitution, both male and female, was legal, public, and widespread - and what we today would consider to be 'pornographic' art was featured among the art collections in respectable upper-class households.

It was considered natural and unremarkable for men to be sexually attracted to teen-aged boys and girls - and pederasty was condoned as long as the younger male partner was not a freeborn Roman.

"Homosexual" and "heterosexual" did not form a part of Roman thinking about sexuality, particularly as no Latin words for these concepts exist.

|

| Master and Slave |

|

| Master and Slave |

Most significantly, Roman attitudes towards sexuality were grounded in the terms 'penetrator' and 'penetrated'.

Male Roman citizens were, by definition, expected to take on the role of 'penetrator, and never be 'penetrated'.

Roman ideals of masculinity were thus premised on taking an 'active role' that was the prime directive of masculine sexual behaviour, as well as political, economic and cultural behaviours for the Roman male citizen.

The impetus toward action might express itself most intensely in an ideal of 'dominance', that reflects the hierarchy of Roman patriarchal society, and the aggression that was responsible for the creation of the Empire.

|

| Penetrator-Penetrated - Binary Model |

It is no accident that one of the most common slang terms for the penis was 'gladius' - the name given to the Roman sword carried by legionaries, and used by gladiators, and male sexual activity was seen as essentially aggressive.

Roman male sexuality should therefore be seen in terms of a "penetrator-penetrated" binary model; that is, the proper way for a Roman male to seek sexual gratification was to insert his penis in his partner.

Allowing himself to be penetrated threatened his liberty as a free citizen, as well as his sexual integrity.

THE ROMAN EMPIRE IN THE MEDIA

The rise and fall of a great empire cannot fail to fascinate us, for we can all see in such a story something of our own times.But of all the empires that have come and gone, none has a more immediate appeal that the Empire of Rome.

It pervades our lives today: its legacy is everywhere to be seen.

It is generally agreed that the Roman Empire was one of the most successful and enduring empires in world history.

Its reputation was successively foretold, celebrated and mourned in classical antiquity.

There has been a long after-life, creating a linear link between Western society today, and the Roman state, reflected in religion, law, political structures, philosophy, art, and architecture.

Because of this, the Roman Empire has become the focus of many fantasies, and much that is imagined and unreal.

Lauded in much modern literature, and even mass media as an exemplary and beneficent power, it was also a bloody and dangerous autocracy.

Rome began as a small town on the Tiber river, and grew into a powerful force for civilization, law, and order in the ancient world.

The Roman Republic, and its successor the Empire, was a federation of teeming cities linked by arrow-straight roads.

Its much lauded but only apparent peace and prosperity - the legendary 'Pax Romanum' - were safeguarded by the powerful legions, that held back the barbarian hordes.

But Rome also had a darker side: the cruelty of mass slavery and the bloody arena, the greed and opulence of the upper class, the unruly mobs pacified by bread and circuses, and the tyranny of many of the emperors, such as Caligula and Nero.

The Empire eventually fell into darkness, but its ghost haunted the Middle Ages, and inspired the Renaissance - and still haunts us today.

|

| Ben Hur |

Part of the blame for the superficial familiarity that our awareness engenders when we think of Rome is the result of plays (from Shakespeare to Shaw, and beyond), books (Lloyd C Douglas, 'The Robe' and Wallace's 'Ben Hur'), and of course the plethora of films, from Cecil B. DeMille right up to the poorly received 'Gladiator'.

The nearest that any works, either in drama, film or literature has ever approached to the 'real Rome' has been the film by Fellini of Pertonius' 'Satyricon', and television series, aptly named 'Rome' - created by John Milius, William J. MacDonald and Bruno Heller.

With the image of Rome such a powerful recurring theme in Western culture, and it is not surprising that it has played such a major role in the cinema, however, it is the film-makers of just three countries who have mainly turned to ancient Rome for inspiration: Italy, the United States, and Britain.

|

| Quo Vadis |

The film industries of France and Germany have rarely upon their countries' distant histories as province or adversary, respectively, of the Roman Empire for filmic themes.

Neither have Spanish film-makers even though the Iberian peninsula settled down to be a loyal province after fiercely resisting Roman conquest for 200 years, even contributing two emperors, Hadrian and Trajan, and the philosopher Seneca.

Of course, the major factor is economics, because historical spectaculars that require the recreation of ancient buildings and cities, and the clothing of thousands of extras in period costumes, have always been extremely expensive.

But other factors are also operative such as culture and differing historical perspectives.

The Roman Empire at its peak of power and territorial extent also coincided with the pivotal event of the formation of European culture - the establishment and expansion of Christianity

The epic story of the birth of Christianity in the eastern extremity of the Roman Empire, and the subsequent spread of Christian teachings to the very heart of the great city of Rome would be an irresistible topic for generations of film-makers in various countries.

The 'Satyricon', however, avoids any mention of Christianity, doubtless because it is based on a 'fantasy novel' actually written by a 'pagan' Roman.

It is a depiction of Roman society at the time of Nero, and is vastly more accurate than, say, 'Quo Vadis' or 'Barabas', which are basically 'plugs' for protestant Christianity, and the 'American Way'.

Fellini Satyricon 'Fellini Satyricon', or simply 'Satyricon', is a 1969 Italian fantasy drama film written and directed by Federico Fellini and somewhat loosely based on Petronius's work 'Satyricon', written during the reign of the emperor Nero and set in imperial Rome. The 'Satyricon Liber' ("The Book of Satyrlike Adventures), is a Latin work of fiction believed to have been written by Gaius Petronius, though the manuscript tradition identifies the author as a certain Titus Petronius. The Satyricon is an example of Menippean satire, which is very different from the formal verse satire of Juvenal or Horace. The work contains a mixture of prose and verse (commonly known as prosimetrum); serious and comic elements; and erotic and homo-erotic passages. As with the 'Metamorphoses' (also called 'The Golden Ass') of Apuleius, classical scholars often describe it as a "Roman novel", without necessarily implying continuity with the modern literary form.

|

| Rome TV Series |

More recently, the television series 'Rome' 1 and 2, has depicted the Empire in a slightly earlier period, at the time of Julius Caesar and his nephew, Gaius Octavian.

Although its chronology was not quite right, and some of the events were, on occasions, invented, its general depiction of ancient Roman culture and society, particularly the aspects of Roman politics, sexuality and violence, was far more accurate than any previous depiction of Ancient Rome.

The Roman Empire, of course, was a pre-Christian society, and was the last great flowering of Classical Civilization.

CHRISTIANITY AND THE EARLY EMPIRE

During the time dealt with in this story (The Story of Gracchus) there were, of course, Christians in the empire.

These were mainly of two kinds - the Jewish Christians, whom most people today would not recognize as Christians.

These Jewish Christians worshiped in the Synagogues, and in the Jerusalem Temple, and it was only their conviction that the Messiah (יהושע) had finally come that distinguished them from their co-religionists.

The other Christians, that could be found in small numbers in Rome, some towns in Italy, and some of the cities of Asia Minor would be equally unrecognisable to today's Christians.

|

| Jesus as 'Helios' |

Their religious writings (those surviving are among the writings of the Hellenized Jew, Paul of Tarsus) made no reference to Nazareth, Bethlehem, 'wise men' from the East, Shepherds, or the long and involved 'passion narrative'.

Their 'Jesus' (Latinized version of יהושע), was a young god who died and then rose again, like Osiris, Dionysus, and Attis .

When they painted his likeness, they did not depict a Jewish rabbi, with long hair and a beard, but a young, cleanly shaved, short-haired god, looking suspiciously like 'Sol Invictus', or the Hellenistic Helios, or they represented him as an equally young, Hellenistic looking god tending his sheep, like the Phrygian god, Attis - and they did not use the symbol of the cross.

Art is silent for the first 150 years of Christianity, with no Christian images being made - but no one knows why there is this lack of imagery. Christian images first start to appear in the 3rd century, in Rome, (long after 'The Story of Gracchus') in the form of funerary art – sarcophagi, wall and ceiling paintings in the catacombs. However, this art concerns itself with the afterlife, not with possible events from the life of Jesus. From its onset, and for its first 200 years, Christian art deliberately avoids the subject of crucifixion.

The very first work of art portraying the crucifixion dates to the 5th century CE.

The numbers of Christians in the Empire however, for a number of centuries, was so small that, contrary to popular imagination, they had very little impact on the social mores of the people in general, and you may be relieved to know that no Christians appear in the 'Story of Gracchus'.

So ..... during the period covered by the 'Story of Gracchus', the Empire is a pre-Christian, 'pagan' society and, as such, is very different from our own society.

Paganism is a term that developed among the Christians of southern Europe during late antiquity to describe religions other than their own. Throughout Christendom, it continued to be used, typically in a derogatory sense. The original word is Latin slang, originally devoid of religious meaning. Itself the word derives from the classical Latin 'pagus' which originally meant 'region delimited by markers', 'paganus' had also come to mean 'of or relating to the countryside', 'country dweller', 'villager'; by extension, 'rustic'. The later use referred to people who followed the religion of the traditional classical gods of Greece and Rome, along with the mores and morals associated with such beliefs.

RECONSTRUCTING ROMAN SOCIETY

In order to produce a believable and, where possible, a realistic story, it has been deemed necessary to reconstruct, in the imagination of both author and reader, Roman society.

This, however, is a task fraught with difficulty.

It was the elite of the Empire, - the emperors, senators, equestrians, and the local elites, - (the magistrates, town and city councillors and priests), who produced almost all the literature and the material culture which we think of as being, essentially, 'Roman'.

|

| The Roman Senate |

- The Roman Senate was, initially the council of the republic, and at first consisted only of one hundred Senators chosen from the Patricians. They were called 'Patres', either on account of their age or the paternal care they had of the state. The word senate derives from the Latin word 'senex', which means "old man". Therefore, senate literally means "board of old men."

- The Equites (Latin: eques nom. singular) constituted the lower of the two aristocratic classes of ancient Rome, ranking below the patricians (patricii), a hereditary caste that monopolized political power during the regal era (753 to 509 BC) and during the early Republic (to 338 BC). A member of the equestrian order was known as an 'eques' (plural: equites).

- Roman magistrates were elected officials in Ancient Rome. Each vicus (city or town neighborhood) elected four local magistrates (vicomagistri) who commanded a sort of local police force chosen from among the people of the vicus by lot. Occasionally the officers of the vicomagistri would feature in certain celebrations (primarily the Compitalia) in which they were accompanied by two lictors

It was the 'Imperial Elite' who stood at the summit of the Roman socio-economic pyramid.

To qualify as part of this elite a person had to be worth more than 400,000 sesterces.

The Sestertius, or Sesterce, (pl. sestertii) was an ancient Roman coin. During the Roman Republic it was a small, silver coin issued only on rare occasions. During the Roman Empire it was a large brass coin. The name Sestertius (originally semis-tertius) means "2 ½", the coin's original value in Asses, and is a combination of semis "half" and tertius "third", that is, "the third half" (0 ½ being the first half and 1 ½ the second half) or "half the third" (two units plus half the third unit, or halfway between the second unit and the third). The Sestertius was also used as a standard unit of account, represented on inscriptions with the monogram HS. Large values were recorded in terms of 'sestertium milia', thousands of Sestertii, with the 'milia' often omitted and implied. The hyper-wealthy general and politician of the late Roman Republic, Crassus (who fought in the war to defeat Spartacus), was said to have had 'estates worth 200 million sesterces'.

Among the possible 50-60 million people in the Roman Empire, at the time of our story, there were probably 5,000 adult men (women were not counted), possessing in excess of 4000,000 sesterces.

An average of 100 adult males in each of the 300 or so cities or major towns in the empire would provide another 30,000 odd very wealthy individuals.

Because of the steep socio-economic gradient in the Roman world, the elite probably held in excess of 80 percent of the total wealth of the empire.

As has been said, it was these individuals who wrote Roman history, either as literature, or in the form of architecture and art - and it is from them that we gain our (possibly distorted) image of ancient Roman civilization.

This story ('The Story of Gracchus') focuses, for much of the narrative on the lives of slaves, and those who have little power or influence - tutors, Roman officers, freedmen, slave traders, gladiators and the like.

There is some information about such people, and with some research we can, to a reasonable extent, reconstruct the lives, hopes and fears of such individuals.

ROMAN NAMES

A lot of rules govern how the Romans take their names.

Traditionally, every male Roman has a nomen, the name of his family line, and a praenomen, which is a personal name that precedes his nomen.

Most of the praenomens are very common, (the Romans were very unimaginative when creating first names), and so few, that Romans tended to write the praenomen as simple initials (so, for example, Quintus Horatius would write his name “Q. Horatius” and Sextus Pompeius would write his “Sex. Pompeius” and Marcus Octavianus Gracchus would be written "M. Octavianus Gracchus").

Noble, rich, distinguished or famous Romans often have at least one cognomen, which described some memorable achievement or characteristic.

After a while, these can become hereditary names in their own right, and sons adopted as heirs to famous families would often take the nomens and cognomens of their own families and their adoptive families as cognomens in their own right. P. Cornelius, for example, had the family cognomen “Scipio.”

When he defeated Hannibal, he gained the name “Africanus” in honor of his campaign.

At some point in the past, Marcus Aurelius Claudius’s family married into the Claudii, which is why he had the nomen Claudius as his cognomen.

When he defeated the Goths at the Battle of Naissus, he also earned the cognomen Gothicus, which he simply attached to the end of his name.

'Plebeian' (plebs - the common people) cognomens tended to be more prosaic, and sometimes obscene.

A butcher might gain a name such as Lucanicus (“sausage”); a criminal or a male prostitute might just as easily have a name such as Encolpius (“arse-crack”).

Cognomens and nomens came in different versions.

Often, they vary by changing the -us or -ius suffix for -inus, -ianus or even -inianus, so, for example, the cognomen Maximus can and does become Maximius, Maximinus, Maximianus and Maximinianus - (Octavian becomes Octavianus, and Vespasian becomes Vespasianus)

A name that ended in - ns - such as Florens or Constans - could change in the same way, only changing the “s” for a “t,” so Florens becomes Florentius, Florentinus, Florentianus and Florentinianus.

Women usually had only their father’s or husband’s nomen, although some had a cognomen as well.

Women’s names could have the same variations, but always ended in -a rather than -us.

Slaves usually only have one name.

This can be their own given name (relatively rare), which could be anything from Athalamer to Joseph to Xystus, depending on where the slave originally came from.

On the other hand, the slave was often given a name by his master - and the name might be more descriptive, such as Myrmex (“ant”) or Onesimus (“useful one”).

In the 'Story of Gracchus' Terentius buys a young slave boy for Gracchus.

Having been simply called 'Boy' for most of his life, the slave has forgotten his real name, and actually has the name 'Boy' - (Pusus).

'Boy' is later given the name 'Aurarius' (meaning golden one - because of the color of his hair), as required in a prophecy from the Cumaean Sibyl.

English-speaking writers sometimes leave the -us from the end of Roman names, so, for example, we often write Pompeius as “Pompey,” Valentinianus as “Valentinian” and “Augustinus” as “Augustin” or “Augustine.”

In the end, most Romans knew each other by only one or two of their names, whether praenomen, nomen or cognomen, no matter how many names they actually had.

M. Aurelius Claudius Gothicus Augustus might be a mouthful, but since everyone simply knew him as Claudius Gothicus, it wasn’t a problem.

Thascius Egnatianus Hostilinus Numida Pestilens is, to his contemporaries, Thascius Hostilinus, or sometimes just Pestilens.

In 'The Story of Gracchus., our main character, Marcus, normally has only three names.

One is his given name - Marcus - two more are from his adoptive father, Octavianus Gracchus.

However, he could legally use Marcus Gaius Agrippa Aelianus Octavianus Gracchus - as he was also entitled to his natural father's names.

Equally his name could be abbreviated to M. Octavianus - which he favoured - relating himself to the 'Divine Augustus'.

Rome was originally a small village on the banks of the River Tiber.

As the years passed, the sheer aggression and drive of the original settlers forged a vast Empire (which in the end they were completely unable to control or direct).

The reason for Rome's aggressive and thrusting rise to power lay in the Roman attitude to morality, which they had inherited from the 'heroic age' of the Hellenic world.

|

| Frederich Nietzsche |

‘Bad’ means ‘lowly’, ‘despicable’, and refers to people who are petty, cowardly, or concerned with what is useful, rather than what is grand or great.

Good-bad identifies a hierarchy of people, the noble masters or aristocracy, and the common people. - in Rome the patricians and the plebeians.

The noble person only recognizes moral duties towards their equals; how they treat people below them is not a matter of morality at all - and this, of course lies at the basis of slavery - a key theme in the 'Story of Gracchus'.

The good, noble person has a sense of ‘fullness’ – of power, wealth, and ability.

From the ‘overflowing’ of these qualities, not from pity, they will help other people, including people below them.

|

| Roman Legion - Master Morality |

‘Good’ originates in self-affirmation, a celebration of one’s own greatness and power.

They revere themselves, and have a devotion for whatever is great.

But this is not self-indulgence: any signs of weakness are despised, and harshness and severity are respected.

A noble morality is a morality of gratitude and vengeance.

Friendship involves mutual respect, and a rejection of over-familiarity, while enemies are necessary, in order to vent feelings of envy, aggression and arrogance.

All these qualities mean that the good person rightly evokes fear in those who are not their equal and a respectful distance in those who are.

This struggle between masters and slaves recurs historically.

According to Nietzsche, ancient Greek and Roman societies were grounded in master morality.

The Homeric hero is the strong-willed man, and the classical roots of the Iliad and Odyssey exemplified Nietzsche's master morality.

Historically, master morality was defeated as the vicious 'slave morality' of Christianity spread throughout the Roman Empire.

ROMANS and RELIGION

In attempting to reconstruct Roman society, it is essential to take into account the immense significance that religion had on Roman attitudes to all aspects of life, from marriage, to sexuality, the family and the home, and most significantly the political decisions taken by the state.

Roman religion was basically 'syncretic', deriving many features from the cults of Latium, Eturia and Alba Longa - the precursor of Rome.

In addition there was the influence of Greek colonies in the south of the Italian peninsular.

From a range of deities adopted from the Greeks, the Romans altered the gods' identities, but left their characters unchanged.

The Greek king of the gods, Zeus, was in Rome the god Jupiter.

Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus The Romans believed that Jupiter granted them supremacy because they had honoured him more than any other people had. Jupiter was "the fount of the auspices upon which the relationship of the city with the gods rested." He personified the divine authority of Rome's highest offices, internal organization, and external relations. The cult of 'Iuppiter Latiaris' was the most ancient known cult of the god: it was practised since very remote times near the top of the Mons Albanus on which the god was venerated as the high protector of the Latin League under the hegemony of Alba Longa.

Jupiter Optimus Maximus

|

| Interior of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus |

Most of the Greek gods could be found in Rome: going through the same drama, the same complications and conflicts.

Both cultures, Greek and Roman, incorporated the idea that the gods were susceptible to making mistakes, much like humans.

Gods and goddesses were just as likely to fall into temptation as mortals, in fact, Roman gods were even prone to sexual liaisons, both heterosexual and homosexual, as their Greek counterparts.

Beginning in the culture of the Greeks, and then moving onward through that of the ancient Romans, there was also a tangled parallelism of human and divine action.

In the absence of rational explanations for what the people of these cultures witnessed around them, it seemed as if everything that happened, good or bad, was due to the intervention of the gods.

Military triumphs were seen as a sign of the celestial rewards, regardless of the comparative strength of the armies involved.

Defeats were seen as an example of divine retribution, and an indication that certain gods demanded to be appeased.

|

| Aeneas |

However, instead of leaving it to happen naturally, Aeneas' mother, the goddess Venus, intervenes.

There were all types of religious and mythological examples found sprinkled throughout Virgil's epic, all leading to the adoption of the mythology and beliefs of the Greeks by Roman society.

Even the fables, actions, and faults have a direct correlation to those that had been believed in Hellas (Greece).

To the Romans, religion was less a spiritual experience than a contractual relationship between mankind and the forces which were believed to control people's existence and well-being.

The result of such religious attitudes were two things: a state cult, which was a significant influence on political and military events of which outlasted the republic, continuing on into the Empire and Principate, and a private concern, in which the head of the family oversaw the domestic rituals and prayers in the same way as the representatives of the people performed the public ceremonials.

As has been stated, to the Roman mind, there was a sacred contract between the gods and the mortals. As part of this agreement each side would provide, as well as receive, services.

The role of the mortal in this partnership with the gods was to worship the gods.

The Romans had many gods of Etruscan origin - one being the goddess Furrina.

All anyone knew was that she was terrible, and thirsty for blood.

Even Cicero could but vaguely guess that she might have been a 'Fury', and yet she had her own flamen (priest), her own priesthood, as befit one who had been one of the first 13 gods of Rome.

Before the Greeks came with their bright, sunlit versions of the myths, the Romans had their own worship.

The three first gods of Rome were bloody Mars (to whom the victorious horse in the Campus Martius chariot races was sacrificed every October 15), death-dealing Jupiter (see above), and Quirinus, a fertility god of sanguinary aspect. (Quirinus’s plant was the myrtle, which prophetically runs with blood when Aeneas plucks it in Book III of Virgil's 'Aeneid'.)

Quirinus’s Quirinal Hill was apparently more prone than most to rains of blood.

Older even than those gods was Terminus, the god of boundaries.

His stone stood on the Capitoline Hill before anything else had been built.

By 500 BCE, the stone stood in the middle of a temple of Jupiter (Jupiter's Stone).

Terminus had refused to move, even for the king of the gods.

His lesser Termini were everywhere that a boundary or cornerstone was needed.

Each Terminal stone rested in a consecrated pit, one where priests had poured blood and ashes; every February 23, on the Terminalia, the stones of Terminus once more drank sacrificial blood.

The Termini remind us of the baetyls, sacred stones inhabited by gods, and perhaps also that Augustus’s first obelisk was made of blood-colored crystalline Imperial porphyry, the same as a pharaoh’s sarcophagus.

Did the stones of Rome move at night, or did some of its statues (of marble cold as death) refresh their vermilion and ocher paint with human gore? Something did.

According to Pausanias, the children of Medea returned from the dead and prowled Corinth - until the city fathers erected a statue of a Lamia.

Something also was reputed to prowl the Roman night - the 'Lemures', the restless dead.

Ovid writes that that “the ancient ritual” of 'Lemuria' “must be performed at night; these dark hours will present due oblations to the silent Shades.”

By Ovid’s time, the ancient ritual consisted of dropping beans behind you and not looking back.

Lemuria took place over three nights in May, which the Etruscans named Amphire.

Amphire (or Ampile) is cognate with Greek ampellos, 'vine', and Roman wine was thick, and sticky and dark red - like blood.

The Romans made the same connection: the Flamen Dialis, the priest of Jupiter, could not drink blood, or eat raw meat or pass under an arbour-vine.

And the Romans feared and embraced Bacchus, the god of wine and of “all the flowing liquids,” in the words of Plutarch.

The Greeks called him Dionysus, with epithets such as Omadius (“Eater of Raw Flesh”), Nyctelius (“God of Night”) and Anthroporraestus (“Man-Slayer”), and knew him also as the god of frenzy and possession, hence as the god of drama.

The Dacians called him 'Zalmoxis', and knew he lived among the dead.

They impaled a human sacrifice every five years to carry him messages.

Be he Dionysus, or Zalmoxis or Bacchus, Rome embraced him.

Almost too fervently at times; the Senate rounded up 7,000 Bacchantes for treason, illicit rites and gross immorality in 186 BCE.

Among the Bacchantes too influential to exile or execute were the Piso family.

They survived and flourished; Julius Caesar’s third wife, Calpurnia, was a Piso.

The Pisonians plotted against Nero to restore the Republic, (just before our story begins) and interestingly, as devotees of the god of the theatre, their conspiracy had some murky connection to the playwright Seneca.

SACRIFICE

|

| Roman Sacrifice |

To perform these ritual correctly was of paramount importance.

One mistake and one would have to begin all over again.

The very nature of Roman religion itself, with its numerous gods, many of which had multiple roles, was cause for problems.

Particularly as in some cases not even the sex of a deity was clear.

Hence the phrase 'whether you be god or goddess' was a widespread in the worship of certain deities.

Many Roman gods also had entire collection of additional names, according to what aspect of life they were a patron to.

So, for example Juno was 'Juno Lucina', in her role of goddess of childbirth, but as goddess of the mint she was known as 'Juno Moneta', (this curious role came about because for a long time the Roman state mint was housed in her temple on the Capitoline hill).

For the official rituals of the state gods it was animals which most of the time were sacrificed, and for each god there would be different animals.

For Janus one sacrificed a ram - for Jupiter it was a heifer (a heifer is a young cow which has not yet had more than one calf).

Mars demanded a ox, a pig and or sheep, except for 15 October when it had to be the winning race horse of the day (the near side horse of a chariot team).

Such animal sacrifices were by their mere nature very elaborate and bloody affairs.

The animal's head had wine and sacred bread sprinkled over it.

The animal was killed by having its throat cut.

It was also disembowelled, for inspection of its internal organs for omens.

The most important organs of the dead beast would then be burnt on the altar.

The rest of the animal was then either moved away, or later eaten as part of a feast.

A priest would then say prayers, or better he would whisper them.

This too was a closely guarded ritual, by which the priest himself would be wearing some form of mask or blindfold to protect his eyes from seeing any evil, and a flute would be played to drown out any evil sounds.

Should anything about the sacrifice go wrong, then it had to be repeated, but only after another, additional, sacrifice had been made to allay any anger of the god about the failure of the first one.

For this purpose one would usually sacrifice a pig.

Thereafter the real sacrifice would be repeated.

Roman religion did not as such really practice human sacrifice.

Although it was not totally unknown. in the third and the second century BC it was the case that slaves were walled up underground by demand of the 'Sibylline Books'.

Also the gladiatorial Munera were a form of sacrifice to the dead.

|

| Gladiatorial Munera |

|

| Gladiatorial Munera |

A further Munera - on a grander scale, follows later in the story (see Chapter XXXI)

In 'Naturales Quaestiones' (Natural Questions), Seneca writes, “Some say that they themselves suspect that there is actually in blood a certain force potent to avert and repel a rain cloud.”

Or to draw one: like calling to like, as below, so above.

High on the hilltops priests of the gods raise their faces to the heavens, waiting for the fat red drops to hit.

The first known rain of blood on Rome occurred during the reign of Romulus, in 737 BCE.

From that time, rains of blood seem to have been regular, though never normal, occurrences, a portent recorded when such things could be spoken of aloud.

Repeated rains of blood fell on the Volcanal, a shrine to Vulcan on the slope of Capitoline Hill.

('I am quite aware that the spirit of indifference which in these days makes men refuse to believe that the gods warn us through portents, also prevents any portents whatever from being either made public or recorded in the annals. But as I narrate the events of ancient times I find myself possessed by the ancient spirit.… Two distinct portents had appeared in the Temple of Fortuna Primigenia on the Quirinal Hill: a palm tree sprang up in the temple precinct and a rain of blood had fallen in the daytime. — Livy, History of Rome - date of such a rain as 181 BCE.)

There was a rain of blood on the Comitium, at the Forum and at the Capitol in 197 BCE during the Macedonian War, and again in 183 BCE, the year Hannibal (lord of the child-burning cult of Carthage) died.

At his approach, the sacred shields of Fortuna in Praeneste sweated blood.

But as Livy mentions above, at some point the portents were no longer “made public or recorded in the annals.”

Perhaps they had become too gruesome, or too frequent for even Imperial historians to dare mention.

But the Romans still knew.

They poured their blood offerings out to the spirits of their ancestors, and to certain of their gods.

The Romans did so in increasing silence, and with increasing circumspection.

They might offer the blood libation into a lake that was known to communicate with the underworld, if they had country estates where such things were situated.

Or, if the Romans were city folk, they had the greatest, most blood-drenched shrine in the world all around them.

ORACLES & AUGURY

Of particular significance in Roman religion was the concept of augury.

According to ancient sources the use of auspices as a means to decipher the will of the gods was more ancient than Rome itself.

|

| Roman Augurer |

Cicero describes in 'De Divinatione' several differences between the auspicial of the Romans and the Etruscan system of interpreting the will of the gods.

|

| The Cumaen Sibyl |

Stoics, for instance, maintained that if there are gods, they care for men, and that if they care for men they must send them signs of their will.

Associated with augurs are the oracles of the gods.

These were numerous, and in some cases renowned in Greece, and included the famous oracle of Apollo at Delphi.

The Romans had their own oracle of Apollo, in this case situated at Cumae, in the person of the Cumaen Sibyl.

Cumae, of course, is very close to Baiae, where, in 'The Story of Gracchus', the Villa Auri is situated and, in the story, Gnaeus Gracchus visits Cumae twice, and receives a significant oracular messages from the Sibyl.

CONCLUSIONS

So ..... when reading the full version of the 'Story of Gracchus', it is wise to take into consideration the great differences between Roman society in the early empire, and current European and American society.

What may seem to us to be immoral, and maybe cruel and sadistic was, to the Romans, simply normal and acceptable behaviour.

This story, therefore, makes no attempt to criticize, condemn or ignore Greco-Roman mores and values, and the narrative accepts, and presents unreservedly the cultural 'status quo' of the times.

If you have any qualms about this, then perhaps this is not a story for you.....

if not... then go to the raunchy, realistic and, a far as possible, an historically accurate serial novel, featuring the adventures of young Markos.

To begin 'The Story of Gracchus' follow the link below

CHAPTER I

(Pirates)

Please note that this chapter contains sexually explicit and violent images and text. If you strongly object to any of these images please contact the blog author at vittoriocarvelli1997@gmail.com and the offending material can be removed. Equally please do not view this chapter if such material may offend.

No comments:

Post a Comment